BANL 6100: Business Analytics

Hyothesis Testing

Mehmet Balcilar

mbalcilar@newhaven.edu

Univeristy of New Haven

2023-09-28 (updated: 2024-11-07)

Testing for Significance

Motivation

Last time, we were introduced to the concept of confidence intervals.

Motivation

Last time, we were introduced to the concept of confidence intervals.

Given how fragile a point estimator is, producing inferences about a population parameter through an interval allows for a more flexible interpretation of a statistic of interest.

Motivation

Last time, we were introduced to the concept of confidence intervals.

Given how fragile a point estimator is, producing inferences about a population parameter through an interval allows for a more flexible interpretation of a statistic of interest.

Now, we move on to a second inferential approach:

- Hypothesis testing

Motivation

Last time, we were introduced to the concept of confidence intervals.

Given how fragile a point estimator is, producing inferences about a population parameter through an interval allows for a more flexible interpretation of a statistic of interest.

Now, we move on to a second inferential approach:

- Hypothesis testing

This procedure serves for determining whether there is enough statistical evidence to confirm a belief/hypothesis about a parameter of interest.

A nonstatistical application of Hypothesis Testing

A nonstatistical application of Hypothesis Testing

When a person is accused of a crime, they face a trial.

A nonstatistical application of Hypothesis Testing

When a person is accused of a crime, they face a trial.

The prosecution presents the case, and a jury must make a decision, based on the evidence presented.

A nonstatistical application of Hypothesis Testing

When a person is accused of a crime, they face a trial.

The prosecution presents the case, and a jury must make a decision, based on the evidence presented.

In fact, what the jury conducts is a test of different hypotheses:

A nonstatistical application of Hypothesis Testing

When a person is accused of a crime, they face a trial.

The prosecution presents the case, and a jury must make a decision, based on the evidence presented.

In fact, what the jury conducts is a test of different hypotheses:

Prior hypothesis: the defendant is not guilty.

Alternative hypothesis: the defendant is guilty.

A nonstatistical application of Hypothesis Testing

The jury does not know which hypothesis is correct.

A nonstatistical application of Hypothesis Testing

The jury does not know which hypothesis is correct.

Their base will be the evidence presented by both prosecution and defense.

A nonstatistical application of Hypothesis Testing

The jury does not know which hypothesis is correct.

Their base will be the evidence presented by both prosecution and defense.

In the end, there are only two possible decisions:

Convict or

Acquit.

Back to Statistics

Statistical hypothesis testing

The same reasoning follows for Statistics:

Statistical hypothesis testing

The same reasoning follows for Statistics:

The prior hypothesis is called the null hypothesis (H0);

The alternative hypothesis is called the research or alternative hypothesis (H1 or Ha).

Statistical hypothesis testing

The same reasoning follows for Statistics:

The prior hypothesis is called the null hypothesis (H0);

The alternative hypothesis is called the research or alternative hypothesis (H1 or Ha).

Putting the trial example in statistical notation:

H0: the defendant is not guilty.

H1: the defendant is guilty.

Statistical hypothesis testing

The same reasoning follows for Statistics:

The prior hypothesis is called the null hypothesis (H0);

The alternative hypothesis is called the research or alternative hypothesis (H1 or Ha).

Putting the trial example in statistical notation:

H0: the defendant is not guilty.

H1: the defendant is guilty.

The hypothesis of the defendant being guilty (H1) is what we are actually testing, since any defendant enters the trial as innocent, until proven otherwise.

Statistical hypothesis testing

The same reasoning follows for Statistics:

The prior hypothesis is called the null hypothesis (H0);

The alternative hypothesis is called the research or alternative hypothesis (H1 or Ha).

Putting the trial example in statistical notation:

H0: the defendant is not guilty.

H1: the defendant is guilty.

The hypothesis of the defendant being guilty (H1) is what we are actually testing, since any defendant enters the trial as innocent, until proven otherwise.

- That is why this is our alternative hypothesis!

Remarks

The testing procedure begins with the assumption that the null hypothesis (H0) is true;

The goal is to determine whether there is enough evidence to infer that the alternative hypothesis (H1) is true.

Stating hypotheses

Stating hypotheses

The first step when doing hypothesis testing is to state the null and alternative hypotheses, H0 and H1, respectively.

Stating hypotheses

The first step when doing hypothesis testing is to state the null and alternative hypotheses, H0 and H1, respectively.

Let us exercise that by practicing with an example.

Stating hypotheses

The first step when doing hypothesis testing is to state the null and alternative hypotheses, H0 and H1, respectively.

Let us exercise that by practicing with an example.

Recall the inventory example from the last lecture.

Stating hypotheses

The first step when doing hypothesis testing is to state the null and alternative hypotheses, H0 and H1, respectively.

Let us exercise that by practicing with an example.

Recall the inventory example from the last lecture.

Now, suppose the manager does not want to estimate the exact (or closest) mean inventory level (μ), but rather test whether this value is different from 350 computers.

Stating hypotheses

The first step when doing hypothesis testing is to state the null and alternative hypotheses, H0 and H1, respectively.

Let us exercise that by practicing with an example.

Recall the inventory example from the last lecture.

Now, suppose the manager does not want to estimate the exact (or closest) mean inventory level (μ), but rather test whether this value is different from 350 computers.

- Is there enough evidence to conclude that μ is not equal to 350 computers?

Stating hypotheses

The first step when doing hypothesis testing is to state the null and alternative hypotheses, H0 and H1, respectively.

Let us exercise that by practicing with an example.

Recall the inventory example from the last lecture.

Now, suppose the manager does not want to estimate the exact (or closest) mean inventory level (μ), but rather test whether this value is different from 350 computers.

- Is there enough evidence to conclude that μ is not equal to 350 computers?

As an important first note, Hypothesis Testing always tests values for population parameters.

Stating hypotheses

The first step when doing hypothesis testing is to state the null and alternative hypotheses, H0 and H1, respectively.

Let us exercise that by practicing with an example.

Recall the inventory example from the last lecture.

Now, suppose the manager does not want to estimate the exact (or closest) mean inventory level (μ), but rather test whether this value is different from 350 computers.

- Is there enough evidence to conclude that μ is not equal to 350 computers?

As an important first note, Hypothesis Testing always tests values for population parameters.

Then, the next step is to know what population parameter the problem at hand is referring to.

Stating hypotheses

Now, consider the following change in the research question for this example:

Stating hypotheses

Now, consider the following change in the research question for this example:

- Is there enough evidence to conclude that μ is greater than 350?

Example

In hypothesis testing, we proceed under the assumption our claim is true and then try to disprove it.

Assume that we have 10 months of Spotify returns. For example we could claim that the average Spotify stock return is 0% against it is different than zero: H0:μ=0 H1:μ≠0

Since the data are drawn from a normal distribution, the sample mean is distributed ¯x∼N(0,110).

Example

In hypothesis testing, we proceed under the assumption our claim is true and then try to disprove it.

Assume that we have 10 months of Spotify returns. For example we could claim that the average Spotify stock return is 0% against it is different than zero: H0:μ=0 H1:μ≠0

Since the data are drawn from a normal distribution, the sample mean is distributed ¯x∼N(0,110).

Now we can use the sampling distribution to comment on how unlikely this claim is.

Example

The z test

The z test

After the hypotheses are properly stated, what do we do?

The z test

After the hypotheses are properly stated, what do we do?

As a simplfying assumption, we will continue to assume that the population standard deviation (σ) is known, while μ is not.

The z test

After the hypotheses are properly stated, what do we do?

As a simplfying assumption, we will continue to assume that the population standard deviation (σ) is known, while μ is not.

- We will relax this hypothesis soon.

The z test

After the hypotheses are properly stated, what do we do?

As a simplfying assumption, we will continue to assume that the population standard deviation (σ) is known, while μ is not.

- We will relax this hypothesis soon.

Another example:

A manager is considering establishing a new billing system for customers. After some analyses, they determined that the new system will be cost-effective only if the mean monthly account is more than US$ 170.00. A random sample of 400 monthly accounts is drawn, for which the sample mean is US$ 178.00. The manager assumes that these accounts are normally distributed, with a standard deviation of US$ 65.00. Can the manager conclude from this that the new system will be cost-effective? Also, they assume a confidence level of 95%.

Another example:

We would like to see if we can disprove this hypothesis that monthly account is more than US$ 170.00 in favor of a claim that there is greater than US$ 170.00 H0:μ=170 H1:μ>170

The z test

After stating the null and alternative hypotheses, we need to calculate a test statistic.

The z test

After stating the null and alternative hypotheses, we need to calculate a test statistic.

Recall the standardization method for a sample statistic:

z=¯x−μσ/√n

The z test

After stating the null and alternative hypotheses, we need to calculate a test statistic.

Recall the standardization method for a sample statistic:

z=¯x−μσ/√n

For hypothesis testing purposes, the above is also known as a z test.

The z test

After obtaining the z value, let us now make use of the confidence level (1 − α) of 95% assumed by the manager.

The z test

After obtaining the z value, let us now make use of the confidence level (1 − α) of 95% assumed by the manager.

This value will be of use to establish a threshold (critical) value in a Standard Normal curve:

The z test

The shaded area is called the rejection region.

The z test

The shaded area is called the rejection region.

If a z statistic falls within the rejection region, our inference is to reject the null hypothesis.

The z test

The shaded area is called the rejection region.

If a z statistic falls within the rejection region, our inference is to reject the null hypothesis.

In case the z value falls outside this region, then we do not reject the null hypothesis.

The z test

The shaded area is called the rejection region.

If a z statistic falls within the rejection region, our inference is to reject the null hypothesis.

In case the z value falls outside this region, then we do not reject the null hypothesis.

- So what is our decision from the example?

The critical value method

The critical value method

What is the critical value?

The critical value method

What is the critical value?Given α=0.5

z_crit <- qnorm(0.05, mean = 0, sd = 1, lower.tail = FALSE)z_crit## [1] 1.644854The critical value method

What is the critical value?Given α=0.5

z_crit <- qnorm(0.05, mean = 0, sd = 1, lower.tail = FALSE)z_crit## [1] 1.644854Calculate the z-score

mu <- 170sigma <- 65n <- 400xbar <- 178z = (xbar-mu)/(sigma/sqrt(n))z## [1] 2.461538The critical value method

What is the critical value?Given α=0.5

z_crit <- qnorm(0.05, mean = 0, sd = 1, lower.tail = FALSE)z_crit## [1] 1.644854Calculate the z-score

mu <- 170sigma <- 65n <- 400xbar <- 178z = (xbar-mu)/(sigma/sqrt(n))z## [1] 2.461538reject_H0 <- z > z_critreject_H0## [1] TRUEThe critical value method

What is the critical value?Given α=0.5

z_crit <- qnorm(0.05, mean = 0, sd = 1, lower.tail = FALSE)z_crit## [1] 1.644854Calculate the z-score

mu <- 170sigma <- 65n <- 400xbar <- 178z = (xbar-mu)/(sigma/sqrt(n))z## [1] 2.461538reject_H0 <- z > z_critreject_H0## [1] TRUEWe do not reject the null that the mean monthly account is more than US$ 170.00.

The p-value method

The p-value method

We may also produce inferences using p-values instead of critical values.

The p-value method

We may also produce inferences using p-values instead of critical values.

The p-value of a statistical test is the probability of observing a test statistic at least as extreme as the one which has been computed, given that H0 is true.

The p-value method

We may also produce inferences using p-values instead of critical values.

The p-value of a statistical test is the probability of observing a test statistic at least as extreme as the one which has been computed, given that H0 is true.

- What is the p-value in our example?

1 - pnorm(q = 2.46, mean = 0, sd = 1)## [1] 0.006946851The p-value method

A p-value of .0069 implies that there is a .69% probability of observing a sample mean at least as large as US$ 178 when the population mean is US$ 170.

The p-value method

A p-value of .0069 implies that there is a .69% probability of observing a sample mean at least as large as US$ 178 when the population mean is US$ 170.

In other words, this value says that we have a pretty good sample statistic for our Hypothesis Testing interests.

The p-value method

A p-value of .0069 implies that there is a .69% probability of observing a sample mean at least as large as US$ 178 when the population mean is US$ 170.

In other words, this value says that we have a pretty good sample statistic for our Hypothesis Testing interests.

However, such interpretation is almost never used in practice when considering p-values.

The p-value method

A p-value of .0069 implies that there is a .69% probability of observing a sample mean at least as large as US$ 178 when the population mean is US$ 170.

In other words, this value says that we have a pretty good sample statistic for our Hypothesis Testing interests.

However, such interpretation is almost never used in practice when considering p-values.

Instead, it is more convenient to compare p-values with the test's significance level (α):

If the p-value is less than the significance value, we reject the null hypothesis;

If the p-value is greater than the significance value, we do not reject the null hypothesis.

The p-value method

Consider, for example, a p-value of .001.

The p-value method

Consider, for example, a p-value of .001.

This number says that we will only start not to reject the null when the significance level is lower than .001.

The p-value method

Consider, for example, a p-value of .001.

This number says that we will only start not to reject the null when the significance level is lower than .001.

- Therefore, this means that it would be really unlikely not to reject the null hypothesis in such situation.

The p-value method

Consider, for example, a p-value of .001.

This number says that we will only start not to reject the null when the significance level is lower than .001.

- Therefore, this means that it would be really unlikely not to reject the null hypothesis in such situation.

We can consider the following ranges and significance features for p-values:

p<.01: highly significant test, overwhelming evidence to infer that H1 is true;

.01≤p≤.05: significant test, strong evidence to infer that H1 is true;

.05<p≤.10: weakly significant test;

p>.10: little or no evidence that H1 is true.

One- and two-tailed tests

One- and two-tailed tests

As you may have already noticed, the typical Normal distribution density curve has two “tails.”

One- and two-tailed tests

As you may have already noticed, the typical Normal distribution density curve has two “tails.”

Depending on the sign present in the alternative hypothesis (H1), our test may have one or two rejection regions.

One- and two-tailed tests

As you may have already noticed, the typical Normal distribution density curve has two “tails.”

Depending on the sign present in the alternative hypothesis (H1), our test may have one or two rejection regions.

Whenever the sign in the alternative hypothesis is either “<” or “>,” we have a one-tailed test.

One- and two-tailed tests

As you may have already noticed, the typical Normal distribution density curve has two “tails.”

Depending on the sign present in the alternative hypothesis (H1), our test may have one or two rejection regions.

Whenever the sign in the alternative hypothesis is either “<” or “>,” we have a one-tailed test.

- For the former case, the rejection region lies on the left tail of the bell curve, whereas for the latter, the rejection region is located on the right tail.

One- and two-tailed tests

A two-tailed test will take place whenever the not equal to sign (≠) is present in the alternative hypothesis.

- This happens because, assuming this sign, the value of our parameter may lie either on the right or on the left tail.

One- and two-tailed tests

A two-tailed test will take place whenever the not equal to sign (≠) is present in the alternative hypothesis.

- This happens because, assuming this sign, the value of our parameter may lie either on the right or on the left tail.

For two-tailed test, we simply divide the significance level (α) by 2.

- Just as with confidence intervals!

Example

Back to the Spotify example:

Lets say we're claiming there is no return on average. We would like to see if we can disprove this hypothesis in favor of a claim that there is a positive return H0:μ=0 H1:μ>0

Clicker Question: What type of hypothesis test is this?

- alternative

- null

- one-sided

- two-sided

Continuing Example

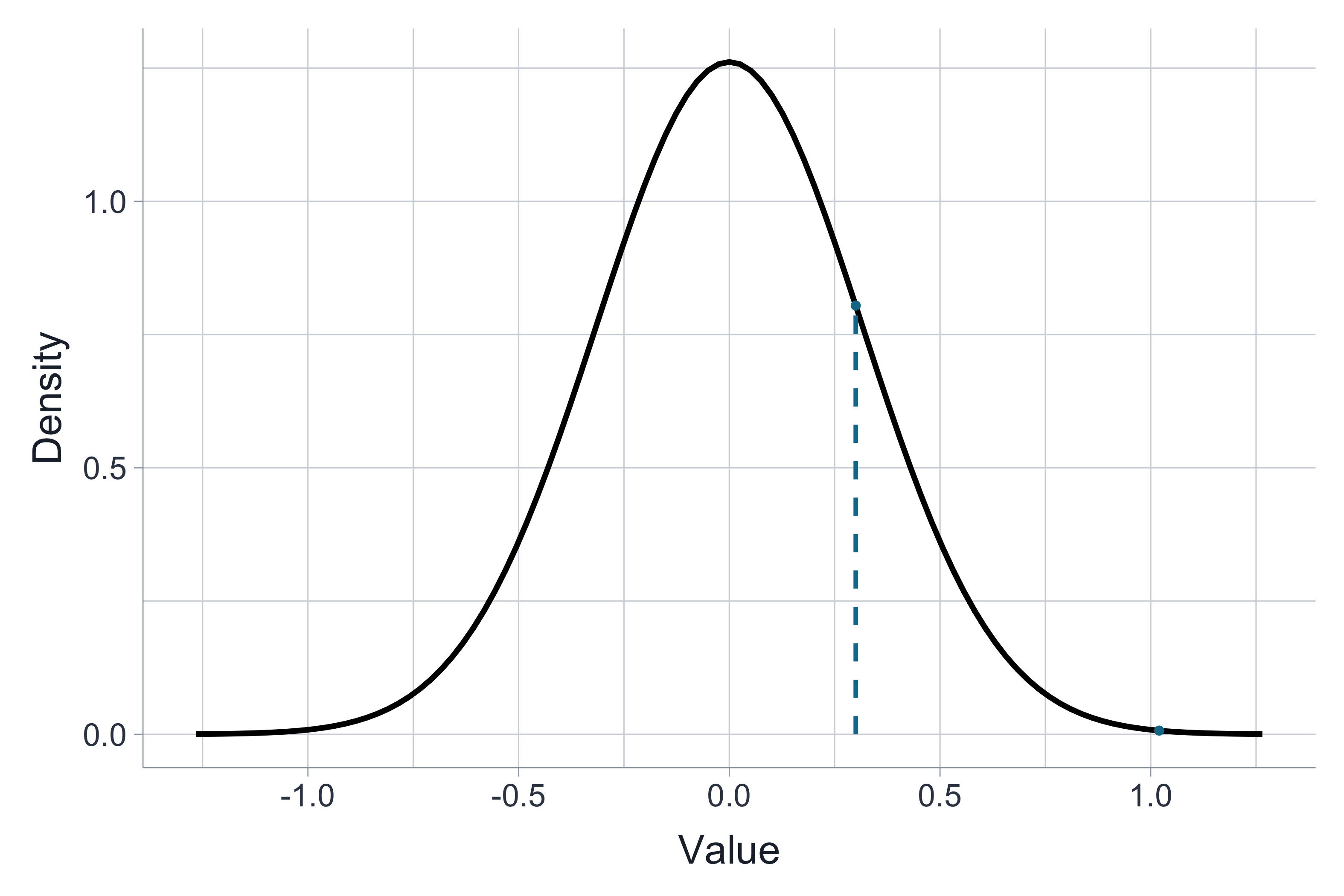

So in the Spotify example, we had 10 observations with a sample mean, ¯x=0.3. We also somehow know that σ2=1.

If we want to test the hypothesis H0:μ=0 H1:μ>0

We want to calculate the probability we got an ¯x as extreme as 0.3 if the true population μ=0. Is it rare that we got 0.3 or is that quite common from the sampling distribution?

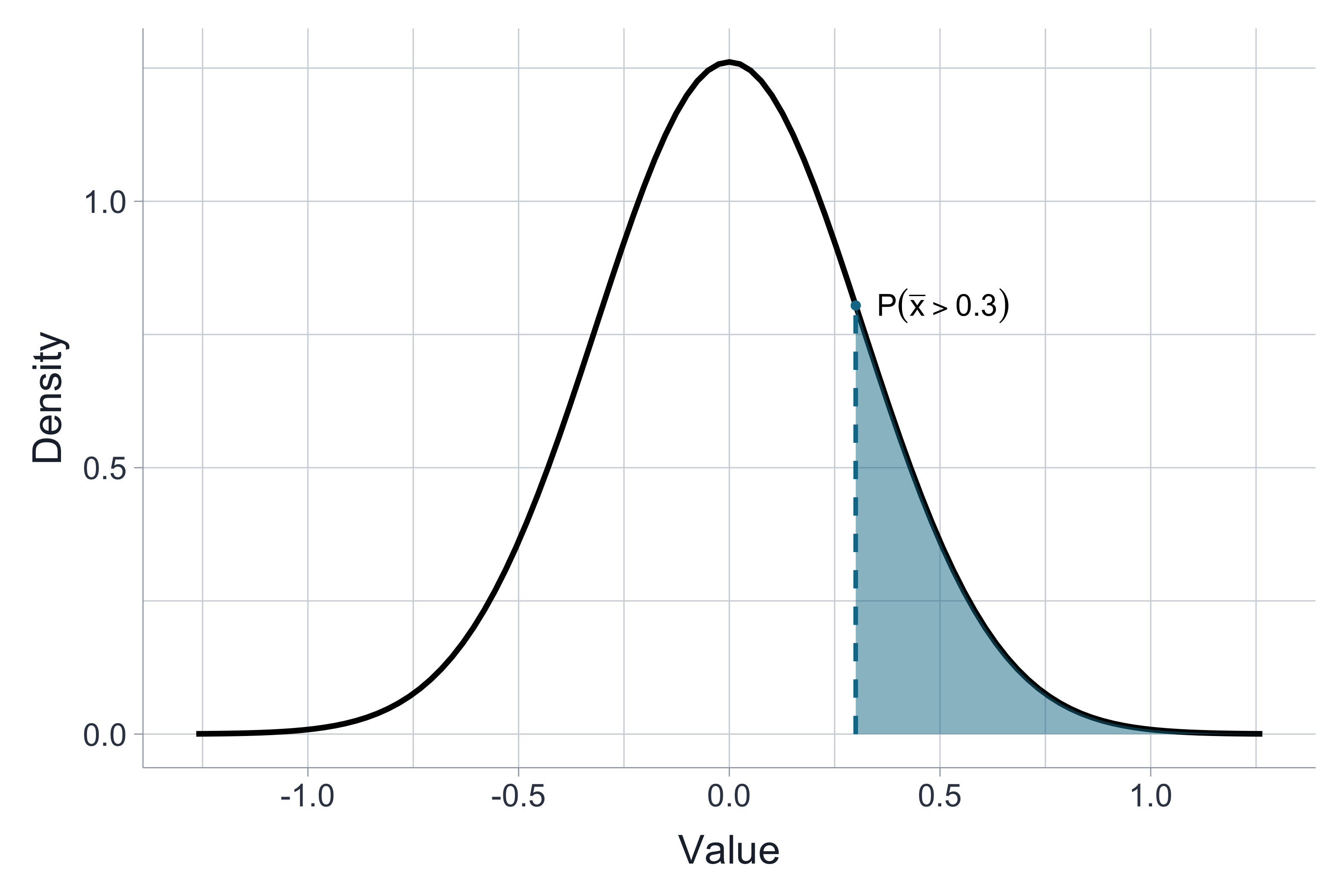

This means we want to calculate P(¯x>0.3) if ¯x∼N(0,110). We will write that as:

P(¯x>0.3 | μ=0)

Continuing Example

We want to calculate P(¯x>0.3) if ¯X∼N(0,110)

Continuing Example

We want to calculate P(¯x>0.3) if ¯X∼N(0,110)

P(¯x>0.3)=P(¯x−μσ/√n>0.3−01/√10)=P(x>0.948)=0.1715

pnorm(q = 0.3, mean = 0, sd = 1/sqrt(10), lower.tail = FALSE)## [1] 0.1713909# orpnorm(0.3/(1/sqrt(10)), mean = 0, sd =1, lower.tail = FALSE)## [1] 0.1713909This says that if the true population mean is μ=0, then 17% of the time we would expect to see a sample mean greater than 0.3, 17% of the time.

This is not so rare (~ 1 out of 5), so this isn't strong evidence against the null.

It doesn't prove it, but it does not rule it out.

Inference about the mean when σ is uknown

Inference when σ is uknown

So far, we have assumed that the population standard deviation (σ) was known when computing confidence intervals and hypothesis testing.

Inference when σ is uknown

So far, we have assumed that the population standard deviation (σ) was known when computing confidence intervals and hypothesis testing.

This assumption, however, is unrealistic.

Inference when σ is uknown

So far, we have assumed that the population standard deviation (σ) was known when computing confidence intervals and hypothesis testing.

This assumption, however, is unrealistic.

Now, we relax such belief, and move on using a very similar approach.

The Student t distribution

The Student t distribution

Recall the formula for the z test:

z=¯x−μσ/√n

The Student t distribution

Recall the formula for the z test:

z=¯x−μσ/√n

Now that the population standard deviation is unknown, what is the best move?

The Student t distribution

Recall the formula for the z test:

z=¯x−μσ/√n

Now that the population standard deviation is unknown, what is the best move?

Replace it by its sample estimator, s!

The Student t distribution

Recall the formula for the z test:

z=¯x−μσ/√n

Now that the population standard deviation is unknown, what is the best move?

Replace it by its sample estimator, s!

t=¯x−μs/√n

The Student t distribution

Now, we do not know the population standard deviation anymore.

The Student t distribution

Now, we do not know the population standard deviation anymore.

However, frequentist methods still assume that the population mean (μ) is normally distributed.

The Student t distribution

Now, we do not know the population standard deviation anymore.

However, frequentist methods still assume that the population mean (μ) is normally distributed.

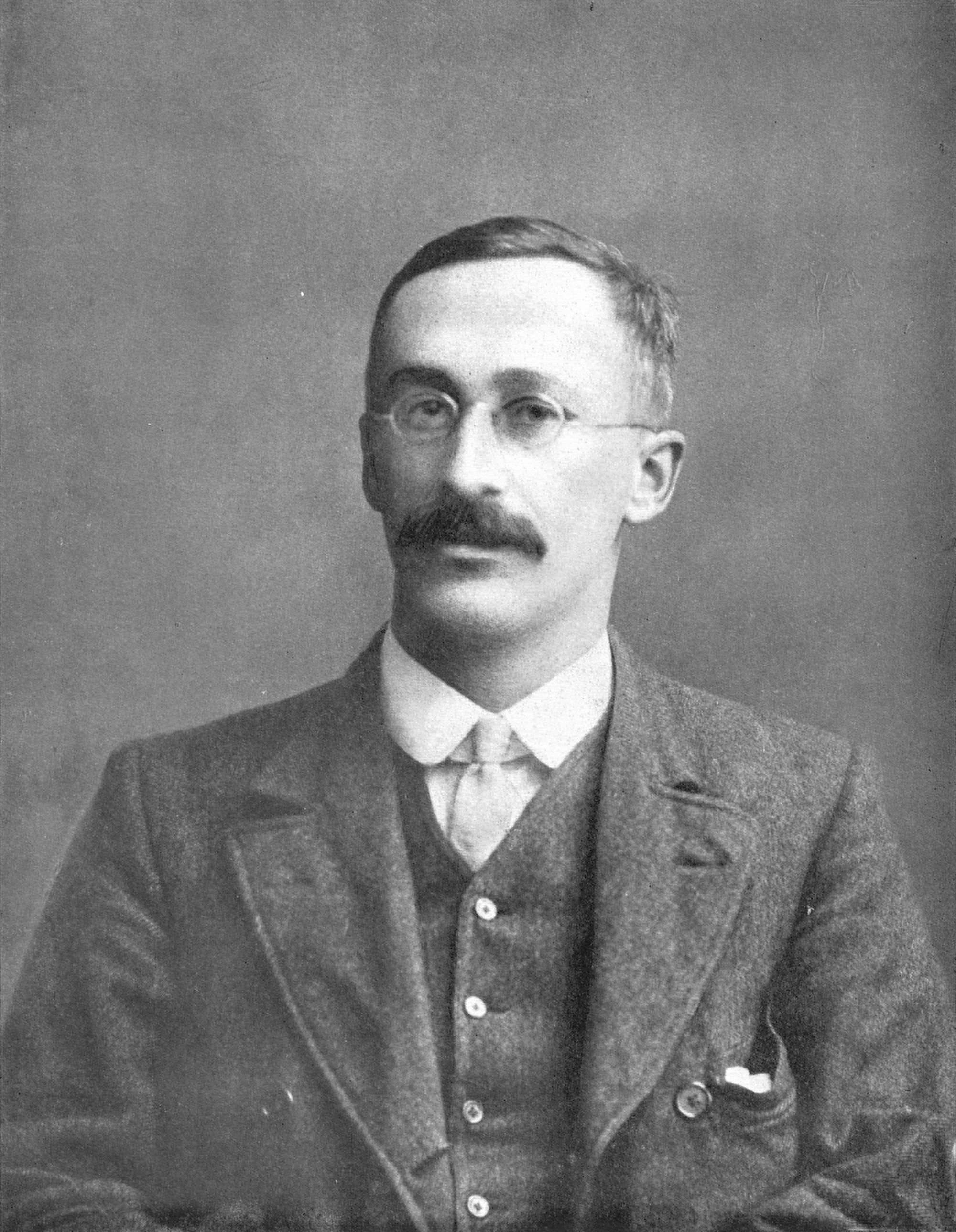

In 1908, William S. Gosset came up with the Student t distribution, whose mean and variance are

E(X)=0

Var(X)=νν−2

where ν=n−1.

The Student t distribution

The t distribution has a "mound-shaped" density curve, while the Normal's is bell-shaped.

The Student t distribution

Its only parameter is ν, the degrees of freedom of the distribution:

X∼t(ν)

The Student t distribution

Its only parameter is ν, the degrees of freedom of the distribution:

X∼t(ν)

The larger the value of ν, the more similar the t distribution is to the Normal.

The Student t distribution

Its only parameter is ν, the degrees of freedom of the distribution:

X∼t(ν)

The larger the value of ν, the more similar the t distribution is to the Normal.

The Student t distribution

When σ is unknown, we can define the confidence interval for the population mean (μ) as:

¯x±tα/2, ν(s√n)

The Student t distribution

When σ is unknown, we can define the confidence interval for the population mean (μ) as:

¯x±tα/2, ν(s√n)

Notice that, in addition to the significance level (α), we also must take the number of degrees of freedom (ν=n−1) into account to find the standard error for ¯x.

The Student t distribution

When σ is unknown, we can define the confidence interval for the population mean (μ) as:

¯x±tα/2, ν(s√n)

Notice that, in addition to the significance level (α), we also must take the number of degrees of freedom (ν=n−1) into account to find the standard error for ¯x.

Furthermore, for hypothesis testing, the t-statistic is obtained with:

t=¯x−μs/√n

The Student t distribution

We cannot use the sampling distribution of μ anymore, since the population standard deviation is unknown.

The Student t distribution

We cannot use the sampling distribution of μ anymore, since the population standard deviation is unknown.

Such assumption considers an infinitely large sample, which is almost never the case in practice.

The Student t distribution

We cannot use the sampling distribution of μ anymore, since the population standard deviation is unknown.

Such assumption considers an infinitely large sample, which is almost never the case in practice.

For smaller sample sizes, the t distribution is extremely useful, and its shape is conditional on this sample size.

The Student t distribution

We cannot use the sampling distribution of μ anymore, since the population standard deviation is unknown.

Such assumption considers an infinitely large sample, which is almost never the case in practice.

For smaller sample sizes, the t distribution is extremely useful, and its shape is conditional on this sample size.

But why (n-1) degrees of freedom?

The Student t distribution

An example:

Assuming that it can be profitable to recycle newspapers, a company’s financial analyst has computed that the firm would make a profit if the mean weekly newspaper collection from each household exceeded 2 lbs. His study collected data from a sample of 148 households. The calculated sample average weight was 2.18 lbs.

Do these data provide sufficient evidence to allow the analyst to conclude that a recycling plant would be profitable? Assume a significance level of 1%, and a sample variance of .962 lbs2.

Solution:

xbar <- 2.18mu <- 2s <- sqrt(0.962)n <- 148df <- n-1alpha <- 0.01t <- (xbar-mu)/(s/(sqrt(n)))1-pt(q = t,df = df)## [1] 0.01354263(1- pt(q = t,df = df)) < 0.01## [1] FALSEWhen to Use Which Distribution

If we have simple random sample, Normal X, and σ known:

- Use z distribution

If we have simple random sample, Normal X, and σ unknown:

- Use the t distribution

What if we don't know that X is normal?

n<15⟹ only use t if X looks very normally distributed.

15<n<31⟹ use t as long as there are no extreme outliers

n>31, probably okay using z

Recall Law of Large numbers that says as n→∞: ¯x−μσ/√n→dN∼(0,1)